History

Stories about the origins of karatedo and the lives of its masters are rich in folklore. The ambiguous nature of these oral traditions can be a problem for scholars, who may be unable to construct a definitive chronology from them, but these stories are the authentic voice of karatedo. Without a sense of the history and philosophy behind karatedo, students cannot understand its meaning.

It is traditional to trace the origins of karatedo to the Indian Buddhist monk Bodhidharma. He is said to have been a member of the Kshatriya or warrior caste who trained in martial arts as a young man before becoming a missionary. After an arduous journey, Bodhidharma arrived in north China in 520 and entered the monastery of the Shaolin Temple (少林寺, Shorinji in Japanese).

Bodhidharma's spiritual practices centered around zazen or seated meditation. So strong was his discipline that he is said to have sat gazing at a wall for nine years. Finding the monks of Shaolin too weak and lethargic to endure his regimen, Bodhidharma taught them a set of breathing and conditioning exercises derived from his martial arts training. These exercises are said to have formed the basis of the fighting arts known as Shaolin quan fa (拳法, kempo).

The legends of Shaolin are a touchstone for the rich and complex history of Chinese martial arts. As they refer to Shorinji Ryu, they are perhaps best understood to be an acknowledgement of the depth and power of Chinese martial traditions as adapted and evolved by the parents of karatedo — the people of Ryukyu (Okinawa).

A chain of islands situated between China, Japan, and southeast Asia, Ryukyu for much of its history has been a maritime nation, central to the exchange of goods, techology, and cultural practices throughout the region. At least as early as the Tang dynasty (618-906), Ryukyu had strong economic and political ties to China, with frequent exchanges of diplomats, tradesmen, and travellers. An equally powerful influence on the islanders was Japan, especially following the 1609 invasion by the Satsuma. In the period that followed, Okinawans were in the uneasy position of being nominal vassals of both China and Japan. This difficult and dynamic situation created a fertile soil for the blossoming of martial arts. A distinctively Okinawan fighting system emerged, known as tode, later called te, okinawate, or karate. The original kanji for karate, 唐手 "china hand," indicate its roots in Chinese traditions.

Many stories tell of Chinese martial artists coming to Okinawa and Okinawans training in China, the most famous of these being Sakugawa, a resident of the town of Shuri who is said to have travelled to China circa 1724 to deepen his knowledge of martial arts. Known for his mastery as Karate Sakugawa, he became famous as a teacher and is claimed by many modern systems of karatedo as a progenitor. The formal name of our style, Sakugawa Koshiki Shorinji-Ryu Karatedo, reflects both its orthodox transmission of Sakugawa's techniques and its descent from the Shaolin arts. From Sakugawa, we are said to inherit the kata Kanku Dai and Sakugawa no Kon and the philosophy of the Dojo Kun.

The Meiji Restoration that launched Japan on a path of modernization and nationalism swept the people of Okinawa in its wake, with Ryukyu officially becoming Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. As Okinawan education and military service became increasingly organized along Western lines, knowledge of karatedo became more widespread, and its public instruction was encouraged.

These social changes transformed karatedo from a closely-held art, practiced only by a few, to a discipline that was taught and discussed in the public sphere. Sakugawa's student "Bushi" Matsumura was a key transitional figure who served as a security specialist for the Okinawan royal family until his retirement, when he began to conduct karatedo classes at Shuri. Not long after his death in 1899, his students Anko Itosu and Chomo Hanashiro were teaching their karatedo in the public schools of Shuri, publishing articles about it, and participating in colloquia with scholars and teachers of other styles. During this period karatedo was strongly influenced by the austere culture of Japanese budo, especially as reflected in modern disciplines such as kendo and judo; from these it gained the organizational frameworks of group training and grading.

Gichin Funakoshi, a student of Itosu, moved to mainland Japan in 1922, beginning the popularization of karatedo there and initiating an exchange of practitioners between Ryukyu and the mainland that continues to this day. Jiro Ogasawara, who studied the art in Okinawa with Chomo Hanashiro, brought our system of Shorinji Ryu to Japan and taught it in parallel with the Ogasawara family's martial arts.

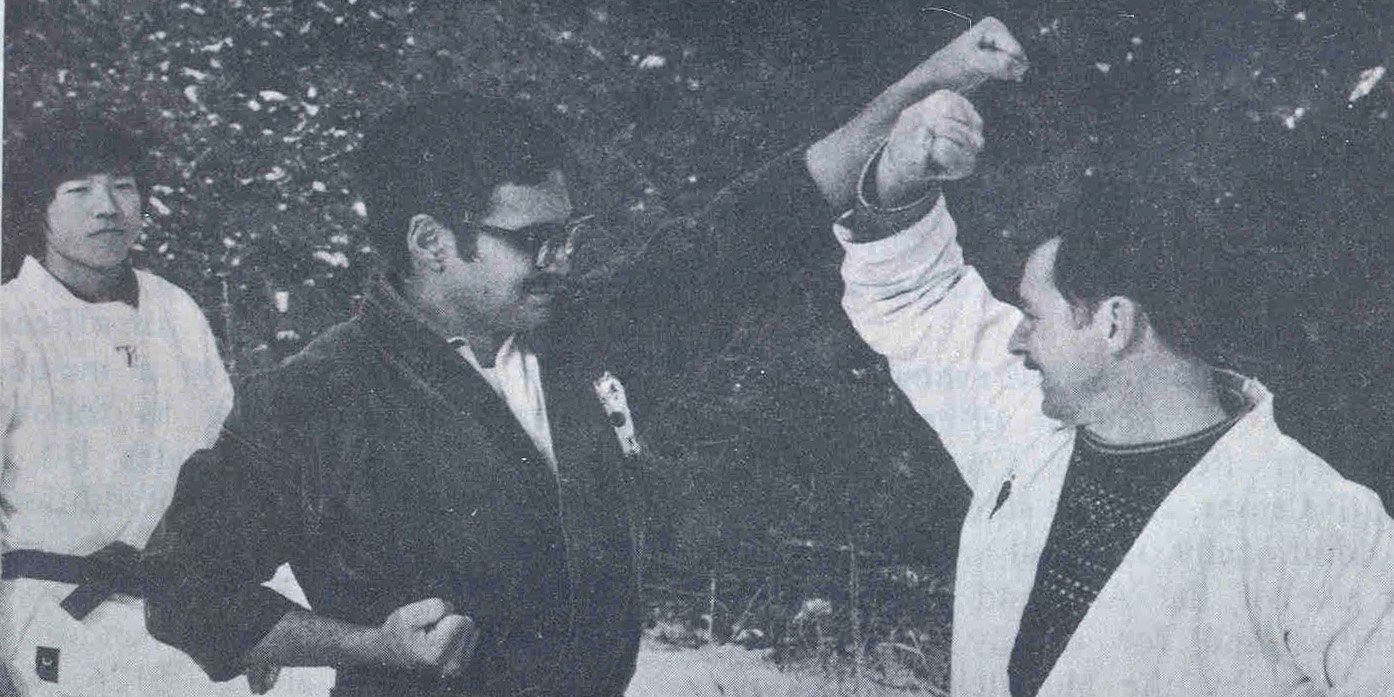

Thomas Cauley, hachidan, received instruction from the Ogasawara family during many tours of military service in Japan and brought the art we now practice to the United States.

Zen philosophy has played an important role in the evolution of karatedo into a practice aiming at personal development. This increased emphasis on spiritual refinement has characterized the transition of many forms of bujutsu (武術, martial techniques) to budo (武道, martial ways), and it is reflected by the modern use of a homonymic kanji to write karatedo as 空手武, "empty hand way." In Karatedo Kyohan, Funakoshi describes the concept of emptiness in terms that evoke Zen attitudes: " ... Just as it is the clear mirror that reflects without distortion, or the quiet valley that echoes a sound, so must one who would study Karatedo purge himself of selfish or evil thoughts, for only with a clear mind and conscience can he understand that which he receives."

For additional information, see also:

- Ideal Teaching: Japanese Culture and the Training Of The Warrior

by Wayne W. Van Horne, Ph.D. - The History, Principles and Precepts of Sakugawa Koshiki Shorinji-Ryu Karate-Do

by Wayne W. Van Horne, Ph.D.